The Rise of Influencer Hijacking

For years, some brands have been attempting to hijack an influencer’s selling power without paying them a penny, explains von Muenster Legal.

There is no denying that certain social media users have the ability to influence the purchasing decisions and behaviours of their followers. It is becoming increasingly evident that brands are trying and succeeding in leveraging this ability by engaging ‘influencers’ to promote their products and services through brand conversations.

This ability has resulted in some influencers being able to establish careers where their income is solely derived from promoting brands on different social media channels for cash, gifts and value in kind.

Given the demonstrated ability of many influencers to reach their followers and communities, and noting that those influencers that can do this sometimes command significant dollars for social media posts, there has been an emergence of businesses and brands that attempt to leverage this influence without the knowledge or permission of the influencer.

Such conduct could be regarded as the ‘hijacking’ of an influencer’s goodwill and reputation, which has often taken the influencer many years to cultivate.

Influencer hijacking attempts have occurred through the unauthorised use of an influencer’s intellectual property, such as appropriating the influencer’s content (for example, videos or photographic images) and reposting that content on the brand’s social media channels. The influencer’s personality is being appropriated, as the posts are able to create the impression that the influencer is associated with or endorsing the brand when in fact they are not.

A simple search through some of the internet’s top names will reveal countless examples of this taking place. Beauty youtuber Tati Westbrook, who has over 9.5 million subscribers, has created a video chronicling a number of times that her image was used in promotions without her permission. Canadian nail artist Simply Nailogical, who has an audience of over 7 million, has taken to watermarking every one of her uploaded images and videos to prevent hijacking – though even this tactic has not been 100% effective.

Additionally, some brands have gone to the extent of altering influencers’ images to make it appear that photos of the influencer genuinely contain the brand’s products. Such conduct is likely to breach a number of laws, including the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) and copyright. In certain circumstances, such conduct could even be defamatory.

In 2017, a situation involving well-known Australian influencer Pia Muehlenbeck arose where a ‘tea detox’ brand chose to leverage Ms Muehlenbeck’s influence by photoshopping their product into photos that Ms Muehlenbeck had uploaded onto her own social media channels, and then uploading the photoshopped photos to their own social media channels. The impression created by the posts was that Ms Muehlenbeck supported and used the brand’s products, which was not the case.

Not only had the brand allegedly used Ms Muehlenbeck’s intellectual property without obtaining her permission, they had completely altered her content to represent to their audience that Ms Muehlenbeck was endorsing and using their product. Understandably, Ms Muehlenbeck was concerned by this conduct and reached out for advice on Twitter. In our view, she could have also reached out for legal advice, as her rights were clearly infringed. Ms Muehlenbeck owned the copyright in the image, which was then scraped, altered and published without her permission, conduct that is a clear breach of copyright under Australian copyright laws.

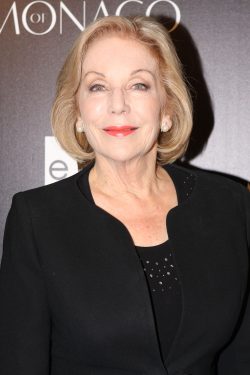

Whilst the hijacking of an influencer’s reputation and goodwill appears to be a relatively recent phenomenon, the unlawful use of celebrities is an established practice that has been addressed by the courts. In the case of Buttrose & Anor v The Senior’s Choice (Australia) Pty Ltd & Anor [2013] FCCA 2050, Ms Buttrose won a case against an aged care franchise who were using her image on its website without her permission. The court found against the franchise for passing off and misleading and deceptive conduct and granted an injunction against its director to prevent use of Ms Buttrose’s image.

Intellectual property and the question of copyright infringement aside, another significant issue to consider is how such conduct could be seen as misleading and deceptive conduct, breaching the ACL. Sections 18 and 29 of the ACL prohibit conduct in trade or commerce that is misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive, or that falsely represents a sponsorship, approval or affiliation with another party that does not exist. The maximum penalty for engaging in such conduct for a company is either $10 million, three times the value of the benefit received for the deceptive conduct, or 10% of the annual turnover for the preceding year (whichever is greater) for each separate instance.

In our view, the tea detox brand’s conduct would be misleading or deceptive because reasonable members of Ms Muehlenbeck’s community would likely believe she was endorsing the brand or had some sort of affiliation or association with the brand. Ms Muehlenbeck’s outrage made it clear that no affiliation, association or endorsement existed, which was reinforced by the fact that the posts in question were brand posts, as opposed to an organic post by Ms Muehlenbeck.

In most instances, outright hijacking of an influencer’s goodwill, personality and content in the circumstances above would be a breach of the ACL and copyright.

Another issue to consider is that if the unauthorised use of the influencer’s goodwill, personality and content by a brand leads to the lowering of the influencer’s reputation in the eyes of reasonable members of the community, this could result in conduct amounting to defamation.

Takeaways

Though influencer hijacking appears to have become somewhat accepted as an inevitability for online celebrities, it is important to note that given the viral effect of social media and the “capacity for proliferation of communications on social media and by internet publication” (as noted in the case of Rebel Wilson v Bauer Media Pty Ltd [2017] VSC 521), hijacking could result in significant damages payable by the hijacker due to the fact that “the defamatory sting might percolate through the internet and social media and contaminate other communications… negatively affecting the [defamed person’s] career”.

Accordingly, it is important for brands, agencies and community managers to only seek to leverage an influencer’s popularity with their community with the influencer’s permission, involving clearly established rules of engagement through, for example, a formal influencer contract.

Importantly, influencers themselves need to be vigilant in order to protect their personalities and influence, and just as many influencers do, immediately correct the record through social media and look to other forms of remedy including legal avenues. Such vigilance helps to ensure that the influencer community remains fair and transparent for brands, agencies, consumers and the influencers themselves.

This article is part of our ongoing Social Series, giving you up-to-date tips about the legal side of using social media. See our other blogs here.