Who owns your #hashtags?

Hashtags have become a powerful social media marketing weapon in the battle for consumer attention and brand engagement online. Thanks to the indexing power of the lowly hash or pound symbol (#) on social media, it is now common for hashtags to take centre stage in the development and execution of advertising campaigns as a tool that can place a brand at the centre of customer conversations.

But while marketers and brands have been effective early adopters of hashtags, the law, as always, has been slow to adapt. In the world of intellectual property and marketing law, the hashtag phenomenon has numerous implications, raising interesting questions such as who ‘owns’ hashtags and how does the law help brands to protect them.

What is a hashtag?

For those who are late to the party, a hashtag is simply a keyword or phrase preceded by the hash symbol (#). Their use was popularised in social media by Twitter when the platform formally adopted hashtags as a means of indexing tweets. They are now a feature of most social media platforms, including Instagram and Facebook. Hashtags categorise messages by aggregating all posts with the same hashtag in real-time, allowing users to search and view related content, for example, to pick some of our favourite topics, #copyright or #defamation (we admit it, we are #nerds).

Hashtags are commonly used to describe or ‘label’ a social media post, for example, someone interested in flying might use the hashtag #pilot. Hashtags also often take on a life of their own and go beyond mere descriptors. For example, hashtags have sometimes become the de facto slogans or taglines at the centre of many online conversations and global social media movements such as #MeToo and #BlackLivesMatter, acting as a loudspeaker amplifying the conversation.

How are marketers using hashtags?

The power of hashtags as an indexing tool has not been lost on savvy brands and their marketing agencies, who have witnessed online conversations develop organically around popular hashtags, without the need for excessive media spending. Developing a ‘viral’ hashtag that leads to increased engagement, traffic and sales can be thought of as the holy grail of social media marketing.

Encouraging the growth of popular hashtags is also big business, with a growing number of brands and agencies partnering with increasingly powerful social media influencers – ‘trend setters’ with large followings on social media – who are paid to post content about the brand’s products and services and get the social media conversation started. Effective hashtag campaigns can also have public relations value, with ‘viral’ campaigns commonly the subject of news reports in the mainstream media, expanding a brand’s reach even further.

There are countless examples of where brands and other organisations have done it well. Famous recent examples include:

- YouTube’s ‘Stay Home #WithMe’ campaign, which creators continue to engage with when sharing videos for users in lockdown throughout COVID-19 outbreaks.

- Dove’s #Showus campaign, which led to over 7 million posts worldwide of users sharing a ‘more inclusive vision of beauty for all media & advertisers to use.’

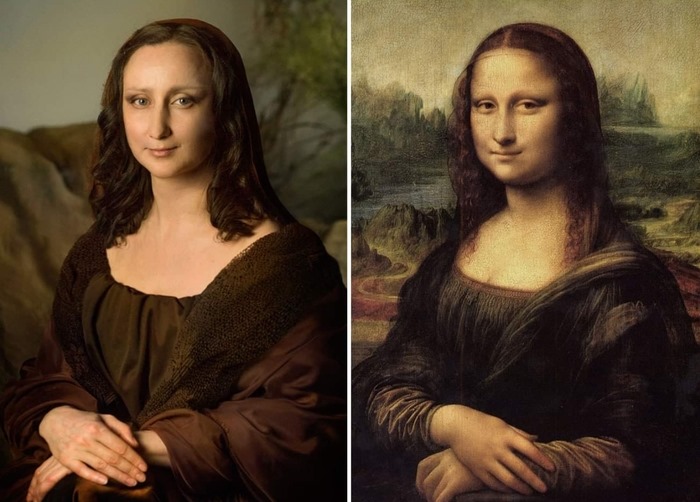

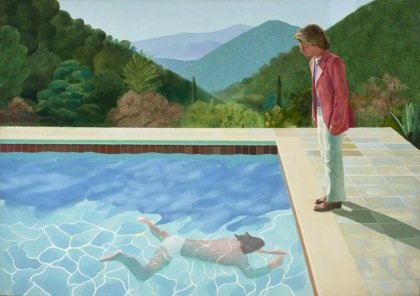

- The viral #gettymuseumchallenge of March 2020, in which people recreated their favourite artworks using objects in their homes:

Image via Krlmhl on Reddit

Images via Steve Roche on Twitter

Social media platforms: the rules of engagement

The popularity of hashtags as a marketing tool has developed as a result of their role as an indexing system on social media. While the system itself is owned by the relevant platform, specific hashtags are generally subject to the same ownership rules as other content posted on social media.

Generally speaking, social media platforms do not claim ownership of user content, but their terms of use usually include a licence for the platform to use the content in certain, and often very broad, ways. Instagram, for example, expressly states in its Terms of Use that it does not “claim ownership” of any content posted on Instagram, but users do grant to Instagram a “non-exclusive, royalty-free, transferable, sub-licensable, worldwide license” to use the content in any media formats through any media channels until it is deleted from Instagram’s systems (other than content that is not shared publicly, which will not be distributed outside Instagram).

While the social media platforms themselves do not claim ownership over the actual wording of a particular hashtag, the person who creates the hashtag does not automatically have the exclusive right to use it. Such a claim could only be made where the relevant creator can establish a legal ownership right, such as via copyright or a trade mark law. None of the major social media platforms impose rules on the ways in which hashtags can to be used, other than limitations on some platforms on the number of hashtags that can be used in each post. Given that neither the social media platform nor the author of the hashtag may be able to claim legal ownership of the hashtag, the result is a Wild West scenario where brands can create their own hashtags, co-opt already popular hashtags or seek to undermine competitor hashtags, seemingly all within the rules of the platform.

This lack of clarity in the social media platform Terms of Use does not mean brands should be too gung-ho about attempting to hijack or dilute a competitor’s hashtag. Risks may still arise out of this conduct, including the potential for trade mark infringement or misleading or deceptive conduct, which in turn may place the brand seeking to undermine a competitor in breach of the platform’s terms of use.

On Instagram, for example, all users warrant that posting content to the platform does not violate the rights of any person, including any intellectual property rights. If a brand is able to assert a legal ownership right over a particular hashtag, such as by way of trade mark registration, it is arguable that a competitor who uses that hashtag to seek to undermine the competition may find themselves in breach of Instagram’s terms of use and the subject of a complaint (not to mention possible legal action for trade mark infringement).

Similarly, as part of Instagram’s Terms of Use, users agree that they must not, in using Instagram, violate any laws in their jurisdiction (including but not limited to copyright laws). In Australia, the Australian Consumer Law prohibits misleading and deceptive conduct and false or misleading representations in trade or commerce. So what happens, for example, where a brand uses a unique hashtag that is specifically associated with another brand or with a particular event, such as #stateoforigin for the State of Origin series? Is that brand falsely implying that it is associated with or sponsoring that event? What if they make numerous posts that all include the same hashtag? As always, the content of the specific post or posts will be the key to answering the question and determining whether a reasonable member of the target audience would understand that the content implied such an association. Brands engaging in such conduct therefore need to be aware that they may well find themselves on the end of a consumer law action and a complaint for breaching the relevant social media platform’s governing rules.

What about copyright?

How can a brand establish an ownership right in a hashtag? Is it even possible?

There has been some speculation as to whether hashtags may be protected under copyright law. In Australia, copyright protection extends automatically to literary, dramatic, musical and artistic works. However, like advertising slogans (State of Victoria v Pacific Technologies (Australia) Pty Ltd (No 2) [2009] FCA 737) and headlines (Fairfax Media Publications Pty Ltd v Reed International Books Australia Pty Ltd [2010] FCA 984), in most cases hashtags are likely to be too short and insubstantial to constitute original ‘literary works’ and therefore are unlikely to attract copyright protection.

While the question of hashtags is yet to be directly considered by the courts, the courts have considered the question of copyright in advertising slogans. Like slogans, marketing hashtags are generally short and snappy, designed to be memorable. In Sullivan v FNH Investments Pty Ltd t/as Palm Bay Hideaway [2003] FCA 323, the court considered the advertising slogans “Somewhere in the Whitsundays” and “the Resort that Offers Precious Little”, finding that the slogans did not demonstrate the requisite degree of judgement, effort and skill to be original literary works in which copyright might subsist. Similar decisions in Australia and abroad reinforce the view that copyright is unlikely to be established in hashtags in the majority of cases.

In the absence of copyright protection, the answer for brands looking to protect their hashtags is much more likely to be found in the law of trade marks.

How to trade mark a #hashtag

In the United States, it is already well established that hashtags are registrable as trade marks where they function as an identifier of the source of the applicant’s goods or services. A similar conclusion is likely in Australia. In fact, a brief review of the trade marks register shows that some brands have already registered trade marks incorporating the word “hashtag”, for example “Hashtag Yolo”, which is registered in relation to energy control devices.

The trend of seeking trade mark protection for hashtags is likely to increase as brands settle upon and build value in hashtags as part of their overall branding.

Section 17 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 defines a trade mark as follows:

“A trade mark is a sign used, or intended to be used, to distinguish goods or services dealt with or provided in the course of trade by a person from goods or services so dealt with or provided by any other person.”

There is no doubt that a hashtag, being the # mark followed by a word or words, is capable of falling within this definition. The question in most cases will therefore become whether the particular hashtag is capable of distinguishing the applicant’s goods or services from those of other traders.

As with any other trade mark, where a trade mark consists of the # symbol followed by descriptive or non-distinctive elements, it will likely not be registrable. For example, #SYDNEY would be rejected as Sydney is a well-known location and should be available for other traders to use to indicate the origin of their goods or services. IP Australia has indicated that other examples such as #PLAYNETBALL for sporting services or #FINDADATE for dating services would run into similar issues. Guidance from IP Australia suggests that, in most cases, the distinguishing element of the trade mark will not be the inclusion of the # symbol, but the words that follow it. Simply placing a # symbol in front of ordinary generic or descriptive words is unlikely to allow you to register them as a trade mark because other trader’s will still need to use those words in the course of business.

However, in some cases it may be arguable that the hashtag itself is an essential part of the company’s branding, especially where the brand has already used the hashtag to such an extent in the market that it has acquired a reputation in the hashtag, with a high degree of consumer recognition. Again, the courts are yet to consider the question directly, but a parallel can be drawn with domain name trade marks, which have been the subject of judicial consideration.

Many brands choose to trade mark their domain name where it forms an essential part of their branding. However, the top level domain (e.g. .com or .com.au) will not normally be the distinctive feature of the trade mark. The website name itself (e.g. ‘Google’ in google.com) must generally be capable of distinguishing the goods or services in order for a trade mark to be registered. In REA Group Ltd v Real Estate 1 Ltd [2013] FCA 5593, however, the Court found that top level domains could be essential elements of a brand. In that case, the Court held that Real Estate 1 had infringed realestate.com.au’s registered composite “realestate.com.au” trade mark on the basis of evidence of widespread consumer recognition of the mark. This evidence supported the proposition that the essential or distinguishing feature of the “realestate.com.au” logo was the domain name in its entirety, rather than simply the words “realestate”. The inclusion of .com.au as part of that essential feature was necessary because “realestate” on its own would not be sufficiently distinctive to establish brand identity, being a term commonly required in the industry. The Court found that the use of “realestate1.com.au” as part of an internet address on a search results page was deceptively similar to the registered “realestate.com.au” trade marks and therefore infringed those trade marks. A similar conclusion may be reached in respect of hashtags, where the hashtag itself becomes an essential feature of the brand recognised in the market, however, this remains to be seen.

Infringing a protected #hashtag

Of course, registering a hashtag trade mark does not necessarily mean that brands will be able to prevent anyone from using their trade mark on social media. To establish infringement, brands would need to show that the competitor had used as a trade mark a substantially identical or deceptively similar sign in relation to the same or closely related goods or services or in relation to unrelated goods or services where the registered trade mark is well known.

One of the key issues likely to arise is whether using a hashtag on social media is use as a trade mark, as a badge of origin to distinguish the brand’s goods or services.

Imagine that a brand had registered as a trade mark a popular hashtag such as #lol in relation to certain goods, say clothing. If another clothing brand were to post on their Twitter account a humorous tweet of a celebrity’s wardrobe malfunction with the #lol included, would that constitute an infringement? In many cases, the answer is likely to be no, because the alleged ‘infringing’ use would merely be use of the hashtag in its ordinary sense, in this case to indicate that the subject matter of the tweet is funny, rather than as a badge of origin (i.e. use as a trade mark). As with potential claims for misleading and deceptive conduct, the answer will usually lie in the content and context of each post.

The courts have considered a similar issue in the context of search engine results and advertising keywords. In Lift Shop Pty Ltd v Easy Living Home Elevators Pty Ltd [2014] FCAFC 75, the court considered whether a composite trade mark featuring the words “LIFT SHOP” was infringed by use of the same words in the title of a webpage, as shown by search results. Lift Shop – the owner of the trade mark – alleged that using the keywords in this way amounted to trade mark infringement. But the court decided that use of the words as keywords “lift shop” was descriptive for the purpose of taking advantage of the operation of search engines, the words being descriptive in the business of selling lifts. Similar conclusions may be reached where brands seek to enforce trade marks over descriptive hashtags. Other brands using the hashtag descriptively for the purposes of taking advantage of a social media platform’s indexing system would be unlikely to constitute use “as a trade mark”. On the other hand, use of a highly distinctive hashtag trade mark may still raise questions of infringement.

Protect your #brand

The law is still catching up with the hashtag phenomenon and it is clear that achieving legal protection for the use of hashtags on social media may require a creative approach.

The primary function of hashtags is to act as an indexing system on social media, which means that, at present, there is no way for brands to filter ‘approved’ brand content (e.g. authorised KFC content featuring the #KFC) from the thousands of unauthorised posts (such as those posted by consumers) that may include the same hashtag. However, as hashtags become more important in the development and execution of advertising campaigns, more brands are expected to consider their options when it comes to protecting and using these potentially valuable assets. Especially where brands develop a distinctive hashtag to be used as a badge of origin, an application to register the hashtag as a trade mark should be considered.

At the same time, brands and their agencies using social media need to carefully consider whether or not they might be infringing someone else’s intellectual property, or running the risk of consumer law infringement or breaching social media platform terms of use, when they create new hashtags and use existing ones, especially when referring to another brand’s assets or where there is potential for consumers to be misled. In any event, the growing importance of hashtags in social media marketing is likely to lead to some interesting battles over the use of these key brand assets (#itson!).